Philosophy

"Amos Vogel, Champion of Films, Dies at 91"

by

Bruce Weber

April 28th, 2012

The New York Times

Amos Vogel, who exerted an influence on the history of film that few other non-filmmakers can claim, founding Cinema 16, which became the nation’s largest membership film society, and directing the first New York Film Festival, died on Tuesday at his home in Greenwich Village. He was 91.

The cause was undetermined, though his kidneys had been failing, his son Steven said.

Cinema 16, the society Mr. Vogel founded in 1947 and ran for 16 years with his wife, Marcia, eventually drew some 7,000 subscribers and provided daring filmmakers from around the world — Roman Polanski, John Cassavetes, Luis Buñuel, Yasujiro Ozu, Robert Bresson, Alain Resnais and Stan Brakhage among them — a place for their work to be screened for American audiences at a time when there were few if any others. It also became a distribution center for experimental films where presenters could find films that had been available only from the filmmakers themselves.

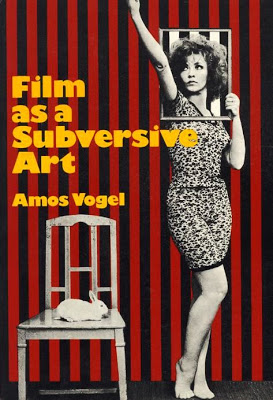

After financial strains forced Cinema 16 to close, Mr. Vogel founded, with Richard Roud, the New York Film Festival, which will present its 50th program this year. As its first director, he gave American audiences their initial exposure to Buñuel’s “Exterminating Angel” and Gillo Pontecorvo’s “Battle of Algiers,” among other films. His 1974 book, “Film as a Subversive Art,” is considered a seminal text dealing with the power of cinema to challenge commonly accepted aesthetic, political, sexual and ideological standards.

“If you’re looking for the origins of film culture in America, look no further than Amos Vogel,” the director Martin Scorsese said last week in a statement to the Film Society of Lincoln Center, which produces the New York festival. He described Mr. Vogel as encouraging him and other filmmakers at the start of their careers and added, “Amos opened the doors to every possibility in film viewing, film exhibition, film curating, film appreciation.”

An Austrian-born Jew who was 17 when his family fled to America, Mr. Vogel had a wry manner and an independent, if not contrarian, bent. A leftist who considered himself a radical — the paid death announcement placed by his sons in The New York Times identified him as a “disenchanted Zionist, Trotskyite, life-long anarchist, loving husband and father” — Mr. Vogel advocated for challenging movies: in other words, the antithesis of postwar Hollywood product.

“The commercialization of art and entertainment is a negative factor in human development,” he said in a 2004 documentary by Paul Cronin, “Film as a Subversive Art: Amos Vogel and Cinema 16.”

A Cinema 16 program was typically a mixed bag. It might include a nature film, a silent narrative film, an account of a scientific study, a political propaganda film, an animated short or an avant-garde visual experiment. The films, Mr. Vogel said, “were always selected from the point of view of how they would collide with each other in the minds of the audience.”

He liked to confront taboos, giving film lovers the opportunity to see things that would be shown nowhere else. One was “The Eternal Jew,” a repellent Nazi propaganda film that argued for the Final Solution. “Even when the message of a film is evil, when it represents the ideology of a particular political group — in fact, one that was strong enough to not only take over a country but then started a world war — it was important to show it,” he said. Amos Vogelbaum was born in Vienna on April 18, 1921. His mother, Mathilde, was a teacher, and his father, Samuel, a lawyer. His father helped kindle young Amos’s interest in movies when he brought home a 9.5-millimeter camera. Young Amos became a Vienna film society member and years later fondly recalled seeing “Night Mail,” a 1936 documentary about a British mail train, and “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” a 1938 film set in the Jazz Age.

Fleeing the Nazis, his family spent several months in Cuba before coming to the United States. Amos, who was determined to make a life in a Jewish homeland, prepared for living on a kibbutz by studying animal husbandry at the University of Georgia. But by 1941 he had abandoned his belief in Zionism and had settled in New York, where he trained as a diamond cutter in the Manhattan jewelry district.

Cinema 16 grew out of his frustration at being unable to see the experimental films he was reading about. Inspired by Maya Deren, a pioneering experimental filmmaker who had taken the unusual step of presenting her own films at the Provincetown Playhouse in Greenwich Village, Mr. Vogel showed his first program there, as well. It included “Monkey Into Man,” a film by Julian Huxley about evolution, and “Lamentation,” a Martha Graham dance film.

His second program included a silent documentary film called “The Private Life of a Cat,“ produced by Deren and her husband, Alexander Hammid, which was banned as obscene because it explicitly showed the birth of kittens. A later program, heavily advertised, almost put the Vogels out of business when a snowstorm kept the audience away. They then decided to turn the society into a members-only club and sell subscriptions, giving them some financial security and allowing them to evade censorship laws that applied to commercial theaters.

Their audience quickly outgrew the Provincetown Playhouse, and Cinema 16 — named for the 16-millimeter film gauge used by most independent filmmakers — eventually moved to the 1,600-seat auditorium of Central High School of Needle Trades (now the High School of Fashion Industries) on West 24th Street.

Mr. Vogel’s wife, the former Marcia Diener, whom he married in 1945, died in 2009. In addition to his son Steven, he is survived by another son, Loring, and four grandchildren.

Mr. Vogel directed the New York Film Festival from 1963 to 1968. He was also director of the film department at Lincoln Center and later a film consultant to Grove Press and National Educational Television. He taught at the Pratt Institute of Art, New York University, Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania, where he was director of film at the Annenberg Center.

In the documentary about him, Mr. Vogel sought to dispel the notion that running a film society was a simple matter of acquiring films and showing them.

“The individual brave enough to venture into this troublesome field,” he said, “must be, no matter what the size of the audience, an organizer, promoter, publicist and copyrighter, businessman, public speaker and artist. A conscientious if not pedantic person versed in mass psychology, he must have roots in his community. And he must know a good film when he sees it.”

Amos Vogel [Wikipedia]

Film as a Subversive Art

Amos Vogel and Cinema 16

by

Amos Vogel

ISBN-10: 1933045272

ISBN-13: 978-1933045276

Film as a Subversive Art was first published in 1974, and has been out of print since 1987. According to Vogel--founder of Cinema 16, North America's legendary film society--the book details the "accelerating worldwide trend toward a more liberated cinema, in which subjects and forms hitherto considered unthinkable or forbidden are boldly explored." So ahead of his time was Vogel that the ideas that he penned some 30 years ago are still relevant today, and readily accessible in this classic volume. Accompanied by over 300 rare film stills, Film as a Subversive Art analyzes how aesthetic, sexual, and ideological subversives use one of the most powerful art forms of our day to exchange or manipulate our conscious and unconscious, demystify visual taboos, destroy dated cinematic forms, and undermine existing value systems and institutions. This subversion of form, as well as of content, is placed within the context of the contemporary world view of science, philosophy, and modern art, and is illuminated by a detailed examination of over 500 films, including many banned, rarely seen, or never released works.

- The Library Of Congress And Silent Films

"Library of Congress study sees troubling loss of silent feature films" The report commissioned by the National Film Preservation Board pinpoints the number of works that have survived. Some movies have been found abroad. by Susan King December 4th,...

- "too Much Johnson" Redux

Joseph Cotton and Edgar Barrier in the 1938 Orson Welles film Too Much Johnson. "Orson Welles lost film screened in Italy" Too Much Johnson, a silent film made by Orson Welles in 1938 and lost for three decades, has been restored and is being screened...

- Deceased--bingham Ray

Bingham RayOctober 1st, 1954 to January 23rd, 2012"Bingham Ray dies at 57; leading force in independent films"Ray, who co-founded October Films, one of the top independent distribution firms in the '90s, suffered a stroke at the Sundance Film Festival.by...

- Deceased--adolfas Mekas

Adolfas Mekas [center] September 30th, 1925 to May 31st, 2011 I only recall seeing two of his films...Hallelujah the Hills [1963] and the The Brig [1964)]..."A ultra-realistic depiction of life in a Marine Corps brig (or jail) at a camp in Japan in 1957....

- "monsters From The Id"--reinvigorate Interest In Science

An event coming mid March at South By Southwest (SXSW) Film Festival in Austin, Texas...David Gargani's Monsters From The Id...and attempt to visually recall the 1950's and 1960's push to get the youth of America interested in science and...

Philosophy

Deceased--Amos Vogel

Amos Vogel

April 18th, 1921 to April 24th, 2012

April 18th, 1921 to April 24th, 2012

"Amos Vogel, Champion of Films, Dies at 91"

by

Bruce Weber

April 28th, 2012

The New York Times

Amos Vogel, who exerted an influence on the history of film that few other non-filmmakers can claim, founding Cinema 16, which became the nation’s largest membership film society, and directing the first New York Film Festival, died on Tuesday at his home in Greenwich Village. He was 91.

The cause was undetermined, though his kidneys had been failing, his son Steven said.

Cinema 16, the society Mr. Vogel founded in 1947 and ran for 16 years with his wife, Marcia, eventually drew some 7,000 subscribers and provided daring filmmakers from around the world — Roman Polanski, John Cassavetes, Luis Buñuel, Yasujiro Ozu, Robert Bresson, Alain Resnais and Stan Brakhage among them — a place for their work to be screened for American audiences at a time when there were few if any others. It also became a distribution center for experimental films where presenters could find films that had been available only from the filmmakers themselves.

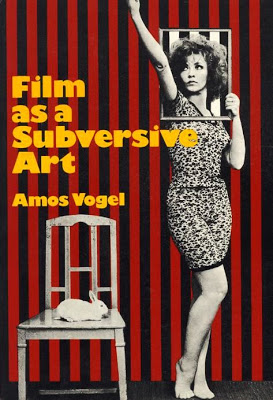

After financial strains forced Cinema 16 to close, Mr. Vogel founded, with Richard Roud, the New York Film Festival, which will present its 50th program this year. As its first director, he gave American audiences their initial exposure to Buñuel’s “Exterminating Angel” and Gillo Pontecorvo’s “Battle of Algiers,” among other films. His 1974 book, “Film as a Subversive Art,” is considered a seminal text dealing with the power of cinema to challenge commonly accepted aesthetic, political, sexual and ideological standards.

“If you’re looking for the origins of film culture in America, look no further than Amos Vogel,” the director Martin Scorsese said last week in a statement to the Film Society of Lincoln Center, which produces the New York festival. He described Mr. Vogel as encouraging him and other filmmakers at the start of their careers and added, “Amos opened the doors to every possibility in film viewing, film exhibition, film curating, film appreciation.”

An Austrian-born Jew who was 17 when his family fled to America, Mr. Vogel had a wry manner and an independent, if not contrarian, bent. A leftist who considered himself a radical — the paid death announcement placed by his sons in The New York Times identified him as a “disenchanted Zionist, Trotskyite, life-long anarchist, loving husband and father” — Mr. Vogel advocated for challenging movies: in other words, the antithesis of postwar Hollywood product.

“The commercialization of art and entertainment is a negative factor in human development,” he said in a 2004 documentary by Paul Cronin, “Film as a Subversive Art: Amos Vogel and Cinema 16.”

A Cinema 16 program was typically a mixed bag. It might include a nature film, a silent narrative film, an account of a scientific study, a political propaganda film, an animated short or an avant-garde visual experiment. The films, Mr. Vogel said, “were always selected from the point of view of how they would collide with each other in the minds of the audience.”

He liked to confront taboos, giving film lovers the opportunity to see things that would be shown nowhere else. One was “The Eternal Jew,” a repellent Nazi propaganda film that argued for the Final Solution. “Even when the message of a film is evil, when it represents the ideology of a particular political group — in fact, one that was strong enough to not only take over a country but then started a world war — it was important to show it,” he said. Amos Vogelbaum was born in Vienna on April 18, 1921. His mother, Mathilde, was a teacher, and his father, Samuel, a lawyer. His father helped kindle young Amos’s interest in movies when he brought home a 9.5-millimeter camera. Young Amos became a Vienna film society member and years later fondly recalled seeing “Night Mail,” a 1936 documentary about a British mail train, and “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” a 1938 film set in the Jazz Age.

Fleeing the Nazis, his family spent several months in Cuba before coming to the United States. Amos, who was determined to make a life in a Jewish homeland, prepared for living on a kibbutz by studying animal husbandry at the University of Georgia. But by 1941 he had abandoned his belief in Zionism and had settled in New York, where he trained as a diamond cutter in the Manhattan jewelry district.

Cinema 16 grew out of his frustration at being unable to see the experimental films he was reading about. Inspired by Maya Deren, a pioneering experimental filmmaker who had taken the unusual step of presenting her own films at the Provincetown Playhouse in Greenwich Village, Mr. Vogel showed his first program there, as well. It included “Monkey Into Man,” a film by Julian Huxley about evolution, and “Lamentation,” a Martha Graham dance film.

His second program included a silent documentary film called “The Private Life of a Cat,“ produced by Deren and her husband, Alexander Hammid, which was banned as obscene because it explicitly showed the birth of kittens. A later program, heavily advertised, almost put the Vogels out of business when a snowstorm kept the audience away. They then decided to turn the society into a members-only club and sell subscriptions, giving them some financial security and allowing them to evade censorship laws that applied to commercial theaters.

Their audience quickly outgrew the Provincetown Playhouse, and Cinema 16 — named for the 16-millimeter film gauge used by most independent filmmakers — eventually moved to the 1,600-seat auditorium of Central High School of Needle Trades (now the High School of Fashion Industries) on West 24th Street.

Mr. Vogel’s wife, the former Marcia Diener, whom he married in 1945, died in 2009. In addition to his son Steven, he is survived by another son, Loring, and four grandchildren.

Mr. Vogel directed the New York Film Festival from 1963 to 1968. He was also director of the film department at Lincoln Center and later a film consultant to Grove Press and National Educational Television. He taught at the Pratt Institute of Art, New York University, Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania, where he was director of film at the Annenberg Center.

In the documentary about him, Mr. Vogel sought to dispel the notion that running a film society was a simple matter of acquiring films and showing them.

“The individual brave enough to venture into this troublesome field,” he said, “must be, no matter what the size of the audience, an organizer, promoter, publicist and copyrighter, businessman, public speaker and artist. A conscientious if not pedantic person versed in mass psychology, he must have roots in his community. And he must know a good film when he sees it.”

Amos Vogel [Wikipedia]

Film as a Subversive Art

Amos Vogel and Cinema 16

Film As A Subversive Art

by

Amos Vogel

ISBN-10: 1933045272

ISBN-13: 978-1933045276

Film as a Subversive Art was first published in 1974, and has been out of print since 1987. According to Vogel--founder of Cinema 16, North America's legendary film society--the book details the "accelerating worldwide trend toward a more liberated cinema, in which subjects and forms hitherto considered unthinkable or forbidden are boldly explored." So ahead of his time was Vogel that the ideas that he penned some 30 years ago are still relevant today, and readily accessible in this classic volume. Accompanied by over 300 rare film stills, Film as a Subversive Art analyzes how aesthetic, sexual, and ideological subversives use one of the most powerful art forms of our day to exchange or manipulate our conscious and unconscious, demystify visual taboos, destroy dated cinematic forms, and undermine existing value systems and institutions. This subversion of form, as well as of content, is placed within the context of the contemporary world view of science, philosophy, and modern art, and is illuminated by a detailed examination of over 500 films, including many banned, rarely seen, or never released works.

- The Library Of Congress And Silent Films

"Library of Congress study sees troubling loss of silent feature films" The report commissioned by the National Film Preservation Board pinpoints the number of works that have survived. Some movies have been found abroad. by Susan King December 4th,...

- "too Much Johnson" Redux

Joseph Cotton and Edgar Barrier in the 1938 Orson Welles film Too Much Johnson. "Orson Welles lost film screened in Italy" Too Much Johnson, a silent film made by Orson Welles in 1938 and lost for three decades, has been restored and is being screened...

- Deceased--bingham Ray

Bingham RayOctober 1st, 1954 to January 23rd, 2012"Bingham Ray dies at 57; leading force in independent films"Ray, who co-founded October Films, one of the top independent distribution firms in the '90s, suffered a stroke at the Sundance Film Festival.by...

- Deceased--adolfas Mekas

Adolfas Mekas [center] September 30th, 1925 to May 31st, 2011 I only recall seeing two of his films...Hallelujah the Hills [1963] and the The Brig [1964)]..."A ultra-realistic depiction of life in a Marine Corps brig (or jail) at a camp in Japan in 1957....

- "monsters From The Id"--reinvigorate Interest In Science

An event coming mid March at South By Southwest (SXSW) Film Festival in Austin, Texas...David Gargani's Monsters From The Id...and attempt to visually recall the 1950's and 1960's push to get the youth of America interested in science and...