Philosophy

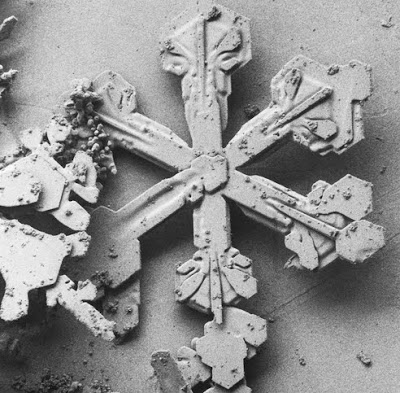

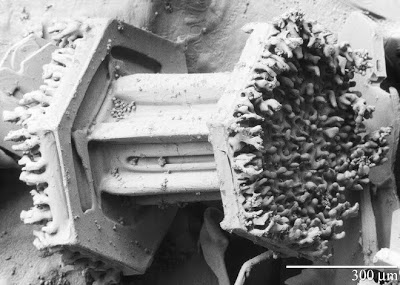

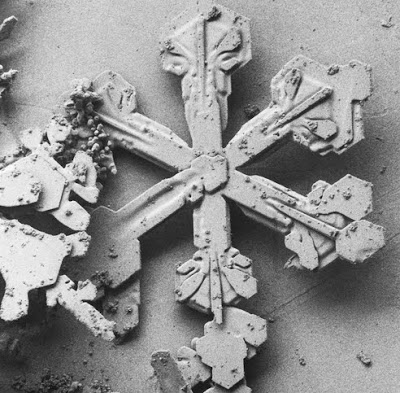

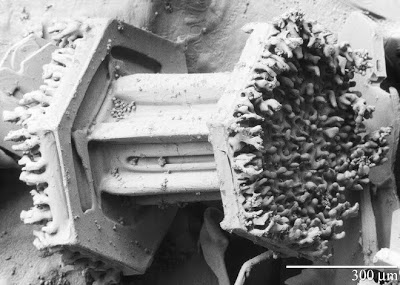

These "...images from the Electron Microscopy Unit of the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center in Beltsville, Maryland."

These "...images from the Electron Microscopy Unit of the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center in Beltsville, Maryland."

It’s been cold out. Really cold, not just normal New York, scarf-and-overcoat December cold but Canadian cold, Arctic cold—the kind of cold that insinuates its way through window frames, and whispers under doors, and chills even perpetually overheated New York apartments. The city may have missed the big snows that have been falling elsewhere in America, crushing the roof of the Metrodome and forcing the Giants into a game in Detroit, but, with the weather this cold, can the snow be too far off?

All this makes the people who cackle with derision at the notion of global warming cackle even more, and though we like to shake our heads at the folly of those who choose to ignore the inarguable proof that this year is one of the hottest years on record—still, at the bone, the human genome does seem to conspire against the truth. In this kind of cold, it is hard to imagine that we will ever be warm again, as though a little genetic amnesia trap had been designed by nature to make us work for the spring to come—to make us plant bulbs and wrap bushes with burlap and light Yule logs and sacrifice virgins, whatever it takes.

In the cold, thoughts turn to snowflakes, heralds of winter. For the past three decades, at this time of year, a twinkling snowflake has been hoisted above the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Fifty-seventh Street. It’s a giant, galumphing thing, which makes the crossroads of the world resemble the main intersection of a Manitoba town. Closer to the office, the local hearth, Starbucks on Forty-second and Sixth, even has a sign that reads, “Friends are like snowflakes: beautiful and different.” This thought seems so comforting, so improving and plural-minded, that one begins to wonder whether it is truly so. Are snowflakes really different—or, rather, how different are they, really?

A quick trip to the New York Public Library and a few request slips (and, let it be said, a little Googling) later, one arrives at the compelling figure of Wilson (Snowflake) Bentley, the great snowflake-ologist, hero of the best movie Frank Capra never made. Bentley was a Vermont semi-recluse who had a lovely and inexplicable devotion to snow. In 1885, at the age of nineteen, he photographed his first snowflake, against a background made as dark as black velvet by long hours spent scraping the emulsion surrounding the snowflake images from the glass-plate negatives. His motives, more than scientific, seem artistic, like those of James Audubon, with his birds, or of Joseph Cornell, with his boxes. On the one hand, there was an urge to document a hidden universe of form and feeling; on the other, a fixation on a small and exquisite world that seemed blissfully different from the workaday one in which Bentley, in Vermont, like Cornell, in Queens, found himself. (Both men were loners, perhaps not coincidentally, who cared for an ailing relative: Cornell for his brother, and Bentley for his mom.) Bentley, over his lifetime, took portraits of five thousand three hundred and eighty-one snow crystals (to give them their proper scientific name; flakes are crystals clumped together) and inserted into the world’s imagination the image of the stellar flower as the typical, “iconic” snowflake, along with the idea of a snowflake’s quiddity, its uniqueness. It is to Bentley that we owe the Fifth Avenue-style snowflake and all those others falling in our minds.

It turns out, however (a few more slips, a bit more Googling), that Bentley censored as much as he unveiled. Most snow crystals—as he knew, and kept quiet about—are nothing like our stellar flower: they’re irregular, bluntly geometric. They are as plain and as misshapen as, well, people. The Fifth Avenue snowflakes are the rare ones, long and lovely, the movie stars and supermodels, the Alessandra Ambrosios of snow crystals. The discarded snowflakes look more like Serras and Duchamps; they’re as asymmetrical as Adolph Gottliebs, and as jagged as Clyfford Stills.

But are they all, as Starbucks insists, at least different? Another flurry of catalogue searching reveals a more cheering, if complex, truth. In 1988, a cloud scientist named Nancy Knight (at the National Center for Atmospheric Research—let’s not defund it) took a plane up into the clouds over Wisconsin and found two simple but identical snow crystals, hexagonal prisms, each as like the other as one twin to another, as Cole Sprouse is like Dylan Sprouse. Snowflakes, it seems, are not only alike; they usually start out more or less the same.

Yet if this notion threatens to be depressing—with the suggestion that only the happy eye of nineteenth-century optimism saw special individuality here—one last burst of searching and learning puts a brighter seasonal spin on things. “As a snowflake falls, it tumbles through many different environments,” an Australian science writer named Karl Kruszelnicki explains. “So the snowflake that you see on the ground is deeply affected by the different temperatures, humidities, velocities, turbulences, etc, that it has experienced on the way.” Snowflakes start off all alike; their different shapes are owed to their different lives.

In a way, the passage out from Snowflake Bentley to the new snowflake stories is typical of the way our vision of nature has changed over the past century: Bentley, like Audubon, believed in the one fixed image; we believe in truths revealed over time—not what animals or snowflakes are, but how they have altered to become what they are. The sign in Starbucks should read, “Friends are like snowflakes: more different and more beautiful each time you cross their paths in our common descent.” For the final truth about snowflakes is that they become more individual as they fall—that, buffeted by wind and time, they are translated, as if by magic, into ever more strange and complex patterns, until, at last, like us, they touch earth. Then, like us, they melt.

A snowflake--something special

Nonphysics of snowflakes

- Are There Really No Two Snowflakes That Are Alike?

It is a common cliché that no two snowflakes are alike. Of course, for every cliché in one direction there is another in the opposite direction. Consider the infinite number of monkeys typing on an infinite number of typewriters, eventually they will...

- Eelctron Microscope And Snowflakes

A snowflake--something special Nonphysics of snowflakes That time of year..."snowflake" talk ...

- Make Your Own Ornaments

Borax Crystal SnowflakeBorax Crystal HeartCopper Plated Holiday OrnamentCrystal Holiday StockingCrystal Paper SnowflakesGlow in the Dark Crystal OrnamentPaper Atom DecorationsSilver Ornaments ...

- That Time Of Year..."snowflake" Talk

We had our first snowfall early in the dark this morning...just a trace. So now we take up snowflakes again. "Snowflake science" December 6th, 2011 R&D We've all heard that no two snowflakes are alike. California Institute of Technology (Caltech)...

- A Snowflake--something Special

Snow Flake "Snow and ice crystals" Highly dendritic snowflakes are an aesthetic source of wonder, but the greater challenge for physicists lies in understanding the "simpler" prismatic and planar forms. by Yoshinori Furukawa and John S. Wettlaufer December...

Philosophy

Snowflake aesthetic

These "...images from the Electron Microscopy Unit of the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center in Beltsville, Maryland."

These "...images from the Electron Microscopy Unit of the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center in Beltsville, Maryland.""All Alike"

by

Adam Gopnik

January 3rd, 2011

The New Yorker

by

Adam Gopnik

January 3rd, 2011

The New Yorker

It’s been cold out. Really cold, not just normal New York, scarf-and-overcoat December cold but Canadian cold, Arctic cold—the kind of cold that insinuates its way through window frames, and whispers under doors, and chills even perpetually overheated New York apartments. The city may have missed the big snows that have been falling elsewhere in America, crushing the roof of the Metrodome and forcing the Giants into a game in Detroit, but, with the weather this cold, can the snow be too far off?

All this makes the people who cackle with derision at the notion of global warming cackle even more, and though we like to shake our heads at the folly of those who choose to ignore the inarguable proof that this year is one of the hottest years on record—still, at the bone, the human genome does seem to conspire against the truth. In this kind of cold, it is hard to imagine that we will ever be warm again, as though a little genetic amnesia trap had been designed by nature to make us work for the spring to come—to make us plant bulbs and wrap bushes with burlap and light Yule logs and sacrifice virgins, whatever it takes.

In the cold, thoughts turn to snowflakes, heralds of winter. For the past three decades, at this time of year, a twinkling snowflake has been hoisted above the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Fifty-seventh Street. It’s a giant, galumphing thing, which makes the crossroads of the world resemble the main intersection of a Manitoba town. Closer to the office, the local hearth, Starbucks on Forty-second and Sixth, even has a sign that reads, “Friends are like snowflakes: beautiful and different.” This thought seems so comforting, so improving and plural-minded, that one begins to wonder whether it is truly so. Are snowflakes really different—or, rather, how different are they, really?

A quick trip to the New York Public Library and a few request slips (and, let it be said, a little Googling) later, one arrives at the compelling figure of Wilson (Snowflake) Bentley, the great snowflake-ologist, hero of the best movie Frank Capra never made. Bentley was a Vermont semi-recluse who had a lovely and inexplicable devotion to snow. In 1885, at the age of nineteen, he photographed his first snowflake, against a background made as dark as black velvet by long hours spent scraping the emulsion surrounding the snowflake images from the glass-plate negatives. His motives, more than scientific, seem artistic, like those of James Audubon, with his birds, or of Joseph Cornell, with his boxes. On the one hand, there was an urge to document a hidden universe of form and feeling; on the other, a fixation on a small and exquisite world that seemed blissfully different from the workaday one in which Bentley, in Vermont, like Cornell, in Queens, found himself. (Both men were loners, perhaps not coincidentally, who cared for an ailing relative: Cornell for his brother, and Bentley for his mom.) Bentley, over his lifetime, took portraits of five thousand three hundred and eighty-one snow crystals (to give them their proper scientific name; flakes are crystals clumped together) and inserted into the world’s imagination the image of the stellar flower as the typical, “iconic” snowflake, along with the idea of a snowflake’s quiddity, its uniqueness. It is to Bentley that we owe the Fifth Avenue-style snowflake and all those others falling in our minds.

It turns out, however (a few more slips, a bit more Googling), that Bentley censored as much as he unveiled. Most snow crystals—as he knew, and kept quiet about—are nothing like our stellar flower: they’re irregular, bluntly geometric. They are as plain and as misshapen as, well, people. The Fifth Avenue snowflakes are the rare ones, long and lovely, the movie stars and supermodels, the Alessandra Ambrosios of snow crystals. The discarded snowflakes look more like Serras and Duchamps; they’re as asymmetrical as Adolph Gottliebs, and as jagged as Clyfford Stills.

But are they all, as Starbucks insists, at least different? Another flurry of catalogue searching reveals a more cheering, if complex, truth. In 1988, a cloud scientist named Nancy Knight (at the National Center for Atmospheric Research—let’s not defund it) took a plane up into the clouds over Wisconsin and found two simple but identical snow crystals, hexagonal prisms, each as like the other as one twin to another, as Cole Sprouse is like Dylan Sprouse. Snowflakes, it seems, are not only alike; they usually start out more or less the same.

Yet if this notion threatens to be depressing—with the suggestion that only the happy eye of nineteenth-century optimism saw special individuality here—one last burst of searching and learning puts a brighter seasonal spin on things. “As a snowflake falls, it tumbles through many different environments,” an Australian science writer named Karl Kruszelnicki explains. “So the snowflake that you see on the ground is deeply affected by the different temperatures, humidities, velocities, turbulences, etc, that it has experienced on the way.” Snowflakes start off all alike; their different shapes are owed to their different lives.

In a way, the passage out from Snowflake Bentley to the new snowflake stories is typical of the way our vision of nature has changed over the past century: Bentley, like Audubon, believed in the one fixed image; we believe in truths revealed over time—not what animals or snowflakes are, but how they have altered to become what they are. The sign in Starbucks should read, “Friends are like snowflakes: more different and more beautiful each time you cross their paths in our common descent.” For the final truth about snowflakes is that they become more individual as they fall—that, buffeted by wind and time, they are translated, as if by magic, into ever more strange and complex patterns, until, at last, like us, they touch earth. Then, like us, they melt.

A snowflake--something special

Nonphysics of snowflakes

Snow Flake

I am a simple person who understands nature

and I am told that "snow flakes" are unique.

I met a "snow flake" who is indeed unique.

A phantom in the heat of a body warm

or a March sunbeam newly born.

Catch this "snow flake" and treasure long

for doubt and confusion will make it gone.

I met a "snow flake" not long ago in physics

no wait that was philosophy, I lie.

A fine blend of beauty and brilliance

that no one could resist

and I was there to assist.

I love my little "snow flake" as I cannot say

for the ears of many I must hold at bay.

I must reserve my love for her secret and

tell no one no way.

2005

I am a simple person who understands nature

and I am told that "snow flakes" are unique.

I met a "snow flake" who is indeed unique.

A phantom in the heat of a body warm

or a March sunbeam newly born.

Catch this "snow flake" and treasure long

for doubt and confusion will make it gone.

I met a "snow flake" not long ago in physics

no wait that was philosophy, I lie.

A fine blend of beauty and brilliance

that no one could resist

and I was there to assist.

I love my little "snow flake" as I cannot say

for the ears of many I must hold at bay.

I must reserve my love for her secret and

tell no one no way.

2005

- Are There Really No Two Snowflakes That Are Alike?

It is a common cliché that no two snowflakes are alike. Of course, for every cliché in one direction there is another in the opposite direction. Consider the infinite number of monkeys typing on an infinite number of typewriters, eventually they will...

- Eelctron Microscope And Snowflakes

A snowflake--something special Nonphysics of snowflakes That time of year..."snowflake" talk ...

- Make Your Own Ornaments

Borax Crystal SnowflakeBorax Crystal HeartCopper Plated Holiday OrnamentCrystal Holiday StockingCrystal Paper SnowflakesGlow in the Dark Crystal OrnamentPaper Atom DecorationsSilver Ornaments ...

- That Time Of Year..."snowflake" Talk

We had our first snowfall early in the dark this morning...just a trace. So now we take up snowflakes again. "Snowflake science" December 6th, 2011 R&D We've all heard that no two snowflakes are alike. California Institute of Technology (Caltech)...

- A Snowflake--something Special

Snow Flake "Snow and ice crystals" Highly dendritic snowflakes are an aesthetic source of wonder, but the greater challenge for physicists lies in understanding the "simpler" prismatic and planar forms. by Yoshinori Furukawa and John S. Wettlaufer December...