Philosophy

by

Matt Novak

April 25th, 2012

BBC NEWS

On 4 October 1957, the Soviet Union hurled a shiny silver ball into space and changed the world forever.

Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite to be put into Earth's orbit, was not only a bold display of military might but also a defining moment for popular culture that stretched far beyond its Kazakhstan launch pad. Almost overnight, everything from toys and clothes to cocktails and film began to incorporate sputnik and space iconography. And the pages of newspapers, as well as reporting on the escalating space race, began to fill with science, technology and futurism-themed comics.

This Saturday, 28 April, I’ll be hosting an event in Los Angeles with BBC Future and Atlas Obscura called Retrofuture: Celebrating a Future That Never Was. It will be a paleofuturist party of sorts, showcasing a range artefacts from my personal collection including many items from this defining period. Amongst the space age toys and others artefacts I have chosen to display some of my favourite comic strips triggered by that Soviet launch, including Closer Than We Think and Our New Age, both of which started just one year after Sputnik soared above the Earth.

Closer Than We Think was illustrated by Detroit-based commercial artist Arthur Radebaugh, who was known for his streamlined-futuristic style, most notably doing illustration work for the automotive industry in Detroit. His techno-utopian sensibilities brought stories of future technologies to life, and helped define the jetpack and flying car futurism that so many people look back fondly on today. At its peak, Closer Than We Think reached 19 million readers every Sunday, exploring everything from the future of education to the mechanisation of war.

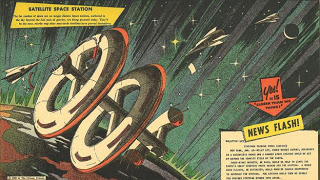

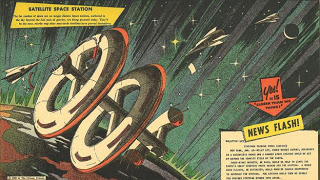

The first strip ran on 12 January 1958 and was appropriately satellite-themed - a pulp-and-ink answer to the soviet launch. The language in the strip was optimistic: “The far reaches of space are no longer distant. Space stations, anchored in the sky beyond the full pull of gravity, are being planned today. They’ll be the next, nearby step after man-made satellites have proved themselves.” The imagery would not look out of place in a Stanley Kubrick film, but the strip was based on the thinking of the time. Specifically it references a report that outlined a plan by a “famed rocket expert” to build a space station orbiting the earth. The module would be built from pieces carried by a “dozen” rockets, he said.

‘Funny fight’

It all sounds very familiar, particularly to a generation that has grown up with Mir and the International Space station. However, it is also a reminder of just how recently these projects – that are so easy to take for granted – were in the realms of fantasy.

The strip would often draw from news stories of the time and extrapolate fantastical technologies. For example, the 11 May 1958 edition of Closer Than We Think took a report from the American Rocket Society about the potential medical benefits of weightlessness and imagined space hospitals “anchored in the heavens”. The strip went on to describe how “one of these hospitals might be shaped like a disc atop elevator tubes leading to the control section. The mushroom-like disc would contain weightless operating rooms for treating heart and other organic troubles as well as bone diseases.”

Of course, the strip did not just focus on space. Sputnik had lit a touch paper on the whole scientific endeavour. For example, the 9 February 1958 edition of the strip took a quote about solar technology from a vice president at the car company Chrysler and imagined the solar powered vehicles of tomorrow: “Tomorrow the sunmobile may replace the automobile. The power of bottled sunshine will propel it. Your solar sedan will take energy from sunrays and store it in accumulators that work like a battery. This power will drive your car just like gasoline does today.”

This broader scientific remit is also evident in Our New Age, a strip dreamt up in 1957 by the dean of the University of Minnesota Institute of Technology, Dr Athelstan Spilhaus, and launched in 1958 with illustrator Earl Cros. Spilhaus wrote the strip and would later joke that he wore out three artists, as Earl Cros was later succeeded by E C Felton and then Gene Fawcette. When Spilhaus stopped writing the strip in 1973, Fawcette continued with Our New Age, at least until 1975.

Dr Spilhaus was very upfront about his desire to get kids interested in science after the launch of Sputnik. He recalled in an interview: “I decided to [start writing the comic strip] right after Sputnik, when I was disturbed about kids knowing very little about science. Rather than fight my own kids reading the funnies, which is a stupid thing to do, I decided to put something good into the comics, something that was more fun and that might give a little subliminal education.”

But it wasn’t just kids that were influenced by Our New Age. After President John F Kennedy appointed Dr Spilhaus to a position directing the science exhibits at the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair, he met with JFK. The president reportedly told Spilhaus at that meeting, “The only science I ever learned was from reading your comic strip in the Boston Globe.” It’s an extraordinary admission, particularly from a president who just a year earlier had announced plans to put an American on the moon.

The 26 September 1965 edition of Our New Age was typical in that it laid out scientific facts and history in the first few panels, and then predicted what modern science might do with future technologies. This strip, on “ultra cold” explained that in 1860 a Scottish scientist had produced a temperature of almost -40 degrees F. By the last panel we see scientists in the year 2165, looking after two people and their dog laying in tubes while in a state of “cryogenic hibernation,” waiting to be brought back to life.

It is easy to dismiss strips like this as simply a technicolor curiosity of an age long gone. However, I believe they offer much more. Pop culture, by its definition, offers a reflection of the interests, preoccupations, fears and desires of the time. The Sputnik launch perfectly exemplifies this – showing an impulsive response to the Soviet’s technological triumph.

The importance of science was suddenly brought home by a distant beep in the skies above the Earth, inspiring a generation to explore new frontiers. And though public opinion polls from the time show that the children of this era were more excited about the prospects of the space age than their parents, the techno-utopian visions of Radebaugh and Spilhaus gave people a window on to these beginnings. The hi-tech world we live in owes a debt to a simple silver sphere that captured the world’s attention more than 50 years ago.

- Kids And Space Art

"How Kids See Space" NASA asks children "to explore how today's technology is bringing tomorrow's dreams closer to reality." by Megan Garber May 21st, 2014 The Atlantic In 1977, a year after the U.S. Bicentennial, the oil company ARCO asked...

- Two Historical Cinematic Halloween Offerings

Above is an example of the two-strip cemented positive process. Film strip A is the black and white negative. Film strip B is the black and white silver record of the red layer. Film strip C is the black and white silver record of the green layer. ...

- Deceased--boris Chertok

Boris Chertok March 1st, 1912 to December 14th, 2011 "Boris Chertok" He helped put first man in space December 15th, 2011 Los Angeles Times Boris Chertok, 99, a Russian rocket designer who played a key role in engineering Soviet-era space programs, died...

- An Idiom..."it's Not Rocket Science"

"It's not rocket science" Meaning It (the subject under discussion) isn't difficult to understand. Origin It is probably no surprise to hear that this phrase is American in origin. Of the English-speaking countries, America was the first to adopt...

- "t-minus: The Race To The Moon"...new Book

T-Minus: The Race to the Moon by Jim Ottaviani Illustrated by Kevin Cannon and Zander Cannon ISBN-10: 1416949607 ISBN-13: 978-1416949602 "From Laika to the Lunar Module" by Jack Shafer July12th, 2009 The New York Times The early space race was really...

Philosophy

Russian cartoons of the future--1958

"Technicolor visions of the future"

by

Matt Novak

April 25th, 2012

BBC NEWS

On 4 October 1957, the Soviet Union hurled a shiny silver ball into space and changed the world forever.

Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite to be put into Earth's orbit, was not only a bold display of military might but also a defining moment for popular culture that stretched far beyond its Kazakhstan launch pad. Almost overnight, everything from toys and clothes to cocktails and film began to incorporate sputnik and space iconography. And the pages of newspapers, as well as reporting on the escalating space race, began to fill with science, technology and futurism-themed comics.

This Saturday, 28 April, I’ll be hosting an event in Los Angeles with BBC Future and Atlas Obscura called Retrofuture: Celebrating a Future That Never Was. It will be a paleofuturist party of sorts, showcasing a range artefacts from my personal collection including many items from this defining period. Amongst the space age toys and others artefacts I have chosen to display some of my favourite comic strips triggered by that Soviet launch, including Closer Than We Think and Our New Age, both of which started just one year after Sputnik soared above the Earth.

Closer Than We Think was illustrated by Detroit-based commercial artist Arthur Radebaugh, who was known for his streamlined-futuristic style, most notably doing illustration work for the automotive industry in Detroit. His techno-utopian sensibilities brought stories of future technologies to life, and helped define the jetpack and flying car futurism that so many people look back fondly on today. At its peak, Closer Than We Think reached 19 million readers every Sunday, exploring everything from the future of education to the mechanisation of war.

The first strip ran on 12 January 1958 and was appropriately satellite-themed - a pulp-and-ink answer to the soviet launch. The language in the strip was optimistic: “The far reaches of space are no longer distant. Space stations, anchored in the sky beyond the full pull of gravity, are being planned today. They’ll be the next, nearby step after man-made satellites have proved themselves.” The imagery would not look out of place in a Stanley Kubrick film, but the strip was based on the thinking of the time. Specifically it references a report that outlined a plan by a “famed rocket expert” to build a space station orbiting the earth. The module would be built from pieces carried by a “dozen” rockets, he said.

‘Funny fight’

It all sounds very familiar, particularly to a generation that has grown up with Mir and the International Space station. However, it is also a reminder of just how recently these projects – that are so easy to take for granted – were in the realms of fantasy.

The strip would often draw from news stories of the time and extrapolate fantastical technologies. For example, the 11 May 1958 edition of Closer Than We Think took a report from the American Rocket Society about the potential medical benefits of weightlessness and imagined space hospitals “anchored in the heavens”. The strip went on to describe how “one of these hospitals might be shaped like a disc atop elevator tubes leading to the control section. The mushroom-like disc would contain weightless operating rooms for treating heart and other organic troubles as well as bone diseases.”

Of course, the strip did not just focus on space. Sputnik had lit a touch paper on the whole scientific endeavour. For example, the 9 February 1958 edition of the strip took a quote about solar technology from a vice president at the car company Chrysler and imagined the solar powered vehicles of tomorrow: “Tomorrow the sunmobile may replace the automobile. The power of bottled sunshine will propel it. Your solar sedan will take energy from sunrays and store it in accumulators that work like a battery. This power will drive your car just like gasoline does today.”

This broader scientific remit is also evident in Our New Age, a strip dreamt up in 1957 by the dean of the University of Minnesota Institute of Technology, Dr Athelstan Spilhaus, and launched in 1958 with illustrator Earl Cros. Spilhaus wrote the strip and would later joke that he wore out three artists, as Earl Cros was later succeeded by E C Felton and then Gene Fawcette. When Spilhaus stopped writing the strip in 1973, Fawcette continued with Our New Age, at least until 1975.

Dr Spilhaus was very upfront about his desire to get kids interested in science after the launch of Sputnik. He recalled in an interview: “I decided to [start writing the comic strip] right after Sputnik, when I was disturbed about kids knowing very little about science. Rather than fight my own kids reading the funnies, which is a stupid thing to do, I decided to put something good into the comics, something that was more fun and that might give a little subliminal education.”

But it wasn’t just kids that were influenced by Our New Age. After President John F Kennedy appointed Dr Spilhaus to a position directing the science exhibits at the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair, he met with JFK. The president reportedly told Spilhaus at that meeting, “The only science I ever learned was from reading your comic strip in the Boston Globe.” It’s an extraordinary admission, particularly from a president who just a year earlier had announced plans to put an American on the moon.

The 26 September 1965 edition of Our New Age was typical in that it laid out scientific facts and history in the first few panels, and then predicted what modern science might do with future technologies. This strip, on “ultra cold” explained that in 1860 a Scottish scientist had produced a temperature of almost -40 degrees F. By the last panel we see scientists in the year 2165, looking after two people and their dog laying in tubes while in a state of “cryogenic hibernation,” waiting to be brought back to life.

It is easy to dismiss strips like this as simply a technicolor curiosity of an age long gone. However, I believe they offer much more. Pop culture, by its definition, offers a reflection of the interests, preoccupations, fears and desires of the time. The Sputnik launch perfectly exemplifies this – showing an impulsive response to the Soviet’s technological triumph.

The importance of science was suddenly brought home by a distant beep in the skies above the Earth, inspiring a generation to explore new frontiers. And though public opinion polls from the time show that the children of this era were more excited about the prospects of the space age than their parents, the techno-utopian visions of Radebaugh and Spilhaus gave people a window on to these beginnings. The hi-tech world we live in owes a debt to a simple silver sphere that captured the world’s attention more than 50 years ago.

- Kids And Space Art

"How Kids See Space" NASA asks children "to explore how today's technology is bringing tomorrow's dreams closer to reality." by Megan Garber May 21st, 2014 The Atlantic In 1977, a year after the U.S. Bicentennial, the oil company ARCO asked...

- Two Historical Cinematic Halloween Offerings

Above is an example of the two-strip cemented positive process. Film strip A is the black and white negative. Film strip B is the black and white silver record of the red layer. Film strip C is the black and white silver record of the green layer. ...

- Deceased--boris Chertok

Boris Chertok March 1st, 1912 to December 14th, 2011 "Boris Chertok" He helped put first man in space December 15th, 2011 Los Angeles Times Boris Chertok, 99, a Russian rocket designer who played a key role in engineering Soviet-era space programs, died...

- An Idiom..."it's Not Rocket Science"

"It's not rocket science" Meaning It (the subject under discussion) isn't difficult to understand. Origin It is probably no surprise to hear that this phrase is American in origin. Of the English-speaking countries, America was the first to adopt...

- "t-minus: The Race To The Moon"...new Book

T-Minus: The Race to the Moon by Jim Ottaviani Illustrated by Kevin Cannon and Zander Cannon ISBN-10: 1416949607 ISBN-13: 978-1416949602 "From Laika to the Lunar Module" by Jack Shafer July12th, 2009 The New York Times The early space race was really...