Philosophy

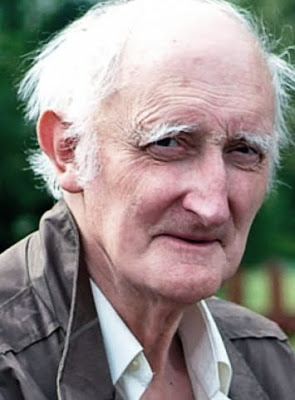

Geoffrey Crawley

Geoffrey Crawley

December 10th, 1926 to October 29th, 2010

"Geoffrey Crawley, 83, Dies; Gently Deflated a Fairy Hoax"

by

Margalit Fox

November 8th, 2010

The New York Times

Were there really fairies at the bottom of the garden, or was it merely a childhood prank gone strangely and lastingly awry?

That, for six decades, was the central question behind the Cottingley fairies mystery, the story of two English schoolgirls who claimed to have taken five pictures of fairy folk in the 1910s and afterward.

Set awhirl by the international news media, the girls’ account won the support of many powerful people, including one of the most famous literary men in Britain. It inspired books and, later on, films, including “Fairy Tale: A True Story” (1997), starring Peter O’Toole, and “Photographing Fairies” (1997), starring Ben Kingsley.

From the start, there were doubters. But there was no conclusive proof of deception until the 1980s, when a series of articles by the English photographic scientist Geoffrey Crawley helped reveal the story for what it was: one of the most enduring, if inadvertent, photographic hoaxes of the 20th century.

A polymath who was variously a skilled pianist, linguist, chemist, inventor and editor, Mr. Crawley died on Oct. 29, at 83, at his home in Westcliff-on-Sea, England.

His death followed a long illness, said Chris Cheesman, news editor of the British magazine Amateur Photographer, which first reported the death on its Web site. At his death, Mr. Crawley was the magazine’s photo science consultant. Survivors include Mr. Crawley’s wife, Carolyn, and son, Thomas.

In a telephone interview on Thursday, Colin Harding, curator of photographic technology at the National Media Museum in Bradford, England, discussed Mr. Crawley’s role in the debunking of the Cottingley fairies case: “He took a scientific and analytical approach that was objective to something that had been previously subjective and so full of emotion,” he said.

The mystery began innocently enough on a summer day in 1917, in Cottingley, a West Yorkshire village. Two cousins, Elsie Wright, then about 16, and Frances Griffiths, about 10, decided to fool their parents by producing pictures of the fairies they claimed to see in the glen near their house.

They borrowed a glass-plate camera belonging to Elsie’s father and returned soon afterward in triumph. Developed, the photograph showed Frances surrounded by whitish forms that resembled stray bits of paper or swans. Their families dismissed the images as childish trickery.

The girls stuck to their story, and later that summer took a second photo, this time of Elsie confronting what appeared to be a gnome. The families remained skeptical but kept the images as private curiosities. They would very likely have remained so had it not been for the intervention of two influential men.

The first was Edward L. Gardner, a leader of the Theosophical Society in Britain, who got wind of the photos in 1920. If they were genuine, he knew, it would advance the cause of theosophy, which believed in the existence of spirit life.

After examining the photos, Mr. Gardner concluded that they were real. Wanting to use them to illustrate his public lectures, he had a darkroom technician produce better-quality negatives. New prints made from them showed the fairies clear as day.

The second man was Arthur Conan Doyle. If anyone should have known better, it was he: a trained physician, he had created the single most rational figure in Western literature and was a skilled amateur photographer.

But Mr. Conan Doyle was also an ardent spiritualist, an interest amplified by his son’s death in World War I. Recruited by Mr. Gardner, Mr. Conan Doyle soon became an impassioned champion of the photos.

For the girls, there was no turning back. In 1920, using cameras supplied by Mr. Gardner and Mr. Conan Doyle, they “took” three more fairy photographs.

That December, Mr. Conan Doyle used two of their photos to illustrate an article in The Strand magazine, “Fairies Photographed: An Epoch-Making Event Described by A. Conan Doyle.” He later wrote a book, “The Coming of the Fairies,” defending the images.

For the next 60 years, public interest in the Cottingley fairies waxed and waned but never completely abated. Over the decades, Elsie and Frances gave interviews in the British press and on television. Each time they were asked whether they had faked the photos, and each time they gave similar answers: coy, charming and wittily evasive.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, empirical investigation of the case began in earnest. The primary investigators, working independently, included James Randi, the magician and professional skeptic; Joe Cooper, an English journalist; and Mr. Crawley.

Geoffrey Crawley was born in London on Dec. 10, 1926. His father was an avid amateur photographer, and as a boy Geoffrey helped him in his darkroom.

A highly gifted pianist, the young Mr. Crawley decided to embark on a concert career before switching course and studying French and German at Cambridge. Accomplished at chemistry, he invented Acutol, a chemical developer for black-and-white film, in the 1960s.

From the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s, Mr. Crawley was editor in chief of the magazine British Journal of Photography. His 10-part series exposing the Cottingley fairy photographs as fakes appeared there in 1982 and 1983.

Mr. Crawley had been asked to determine the authenticity of the photos in the late 1970s. “My instant reaction was amusement that it could be thought that the photographs depicted actual beings,” he wrote in 2000.

But he came to believe, as he wrote, that “the photographic world had a duty, for its own self-respect,” to clarify the record.

Mr. Harding of the National Media Museum said of Mr. Crawley: “He set the same approach to the Cottingley fairies as with any assignment, be it testing a new chemical or a new lens. What he did was take everything back to empirical principles, ignore everything that had been written previously, go back to the actual cameras, the actual prints, and analyze them in a way that would inform something that was objective.”

After acquiring the original cameras, Mr. Crawley painstakingly tested whether they were capable of producing images as crisp and recognizable as those popularized by Mr. Gardner and Mr. Conan Doyle. In the end he determined that they were not, and that the darkroom alchemy ordered by Mr. Gardner had transformed the girls’ amateurish blurs into marketable fairies.

In the early 1980s, amid the renewed attention, the cousins came clean. They first confessed privately to Mr. Cooper in interviews for his series in The Unexplained, a British periodical about the paranormal. In 1983, they admitted the hoax in The Times of London.

The girls’ plan had been absurdly simple: they used fairy illustrations from a book, which Elsie, a gifted artist, copied onto cardboard, cut out and stuck into the ground with hatpins. They had never set out to deceive anyone beyond their own families.

To the end of her life, Frances, who died in 1986, maintained that the fifth photo in the series was genuine. Elsie, who died in 1988, said that all were fakes.

Two of the three cameras used by the girls are now on permanent display at the National Media Museum in Bradford.

In the course of his work, Mr. Crawley befriended Elsie, then in her 80s. His writings about the hoax, though rigorously scientific, display great tenderness toward the two country girls whose idle boast of seeing magical creatures captivated a nation convulsed by war and modernity.

“Of course there are fairies — just as there is Father Christmas,” Mr. Crawley wrote in the British Journal of Photography in 2000. “The trouble comes when you try to make them corporeal. They are fine poetic concepts taking us out of this at times too ugly real world.”

“At least,” he went on to say, “Elsie gave us a myth which has never harmed anyone.”

“How many professed photographers,” he added, “can claim to have equaled her achievement with the first photograph they ever took?”

Geoffrey Crawley

Adjusted Physics?

Sir Arthur Doyle...Spiritualism...Cottington Fairies

- Sherlock Holmes And Chemistry

"Sherlock Holmes knew chemistry" by James F. O’Brien April 8th, 2013 Oxford University Press Sir Arthur Conan Doyle claimed that he wrote the Sherlock Holmes stories while waiting in his medical office for the patients who never came. When this...

- The Strand Magazine...january 1891 To March 1950...711 Issues

Agatha Christie, H. G. Wells, P. G. Wodehouse, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle were published in this quarterly journal.The Strand Magazine [Wikipedia]Here is a complete issue...January to June 1895...

- Deceased--leroy Grannis

LeRoy Grannis August 12th, 1917 to February 3rd, 2011 "LeRoy Grannis dies at 93; photographer documented California surf culture of the 1960s and '70s" The images by photographer LeRoy Grannis helped popularize and immortalize the sport —and...

- A Swiss Doyle

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle May 22nd, 1859 to July 7th, 1930 Scottish novelist, physician, spiritualist. His fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes, emulates the scientist, diligently searching through data and to make sense of it. "It is a capital mistake...

- Adjusted Physics?

I am sure you will agree that most of the so-called paranormal material is focused on entertainment and the acquisition of bucks. That doesn't mean that there aren't events that are truly “odd or unusual”--beyond the range of current knowledge...

Philosophy

Deceased--Geoffrey Crawley

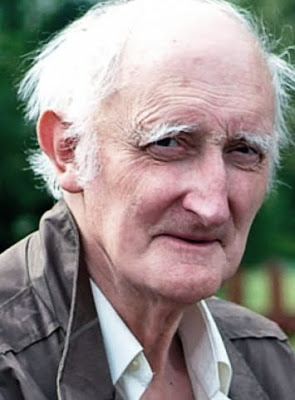

Geoffrey Crawley

Geoffrey CrawleyDecember 10th, 1926 to October 29th, 2010

"Geoffrey Crawley, 83, Dies; Gently Deflated a Fairy Hoax"

by

Margalit Fox

November 8th, 2010

The New York Times

Were there really fairies at the bottom of the garden, or was it merely a childhood prank gone strangely and lastingly awry?

That, for six decades, was the central question behind the Cottingley fairies mystery, the story of two English schoolgirls who claimed to have taken five pictures of fairy folk in the 1910s and afterward.

Set awhirl by the international news media, the girls’ account won the support of many powerful people, including one of the most famous literary men in Britain. It inspired books and, later on, films, including “Fairy Tale: A True Story” (1997), starring Peter O’Toole, and “Photographing Fairies” (1997), starring Ben Kingsley.

From the start, there were doubters. But there was no conclusive proof of deception until the 1980s, when a series of articles by the English photographic scientist Geoffrey Crawley helped reveal the story for what it was: one of the most enduring, if inadvertent, photographic hoaxes of the 20th century.

A polymath who was variously a skilled pianist, linguist, chemist, inventor and editor, Mr. Crawley died on Oct. 29, at 83, at his home in Westcliff-on-Sea, England.

His death followed a long illness, said Chris Cheesman, news editor of the British magazine Amateur Photographer, which first reported the death on its Web site. At his death, Mr. Crawley was the magazine’s photo science consultant. Survivors include Mr. Crawley’s wife, Carolyn, and son, Thomas.

In a telephone interview on Thursday, Colin Harding, curator of photographic technology at the National Media Museum in Bradford, England, discussed Mr. Crawley’s role in the debunking of the Cottingley fairies case: “He took a scientific and analytical approach that was objective to something that had been previously subjective and so full of emotion,” he said.

The mystery began innocently enough on a summer day in 1917, in Cottingley, a West Yorkshire village. Two cousins, Elsie Wright, then about 16, and Frances Griffiths, about 10, decided to fool their parents by producing pictures of the fairies they claimed to see in the glen near their house.

They borrowed a glass-plate camera belonging to Elsie’s father and returned soon afterward in triumph. Developed, the photograph showed Frances surrounded by whitish forms that resembled stray bits of paper or swans. Their families dismissed the images as childish trickery.

The girls stuck to their story, and later that summer took a second photo, this time of Elsie confronting what appeared to be a gnome. The families remained skeptical but kept the images as private curiosities. They would very likely have remained so had it not been for the intervention of two influential men.

The first was Edward L. Gardner, a leader of the Theosophical Society in Britain, who got wind of the photos in 1920. If they were genuine, he knew, it would advance the cause of theosophy, which believed in the existence of spirit life.

After examining the photos, Mr. Gardner concluded that they were real. Wanting to use them to illustrate his public lectures, he had a darkroom technician produce better-quality negatives. New prints made from them showed the fairies clear as day.

The second man was Arthur Conan Doyle. If anyone should have known better, it was he: a trained physician, he had created the single most rational figure in Western literature and was a skilled amateur photographer.

But Mr. Conan Doyle was also an ardent spiritualist, an interest amplified by his son’s death in World War I. Recruited by Mr. Gardner, Mr. Conan Doyle soon became an impassioned champion of the photos.

For the girls, there was no turning back. In 1920, using cameras supplied by Mr. Gardner and Mr. Conan Doyle, they “took” three more fairy photographs.

That December, Mr. Conan Doyle used two of their photos to illustrate an article in The Strand magazine, “Fairies Photographed: An Epoch-Making Event Described by A. Conan Doyle.” He later wrote a book, “The Coming of the Fairies,” defending the images.

For the next 60 years, public interest in the Cottingley fairies waxed and waned but never completely abated. Over the decades, Elsie and Frances gave interviews in the British press and on television. Each time they were asked whether they had faked the photos, and each time they gave similar answers: coy, charming and wittily evasive.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, empirical investigation of the case began in earnest. The primary investigators, working independently, included James Randi, the magician and professional skeptic; Joe Cooper, an English journalist; and Mr. Crawley.

Geoffrey Crawley was born in London on Dec. 10, 1926. His father was an avid amateur photographer, and as a boy Geoffrey helped him in his darkroom.

A highly gifted pianist, the young Mr. Crawley decided to embark on a concert career before switching course and studying French and German at Cambridge. Accomplished at chemistry, he invented Acutol, a chemical developer for black-and-white film, in the 1960s.

From the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s, Mr. Crawley was editor in chief of the magazine British Journal of Photography. His 10-part series exposing the Cottingley fairy photographs as fakes appeared there in 1982 and 1983.

Mr. Crawley had been asked to determine the authenticity of the photos in the late 1970s. “My instant reaction was amusement that it could be thought that the photographs depicted actual beings,” he wrote in 2000.

But he came to believe, as he wrote, that “the photographic world had a duty, for its own self-respect,” to clarify the record.

Mr. Harding of the National Media Museum said of Mr. Crawley: “He set the same approach to the Cottingley fairies as with any assignment, be it testing a new chemical or a new lens. What he did was take everything back to empirical principles, ignore everything that had been written previously, go back to the actual cameras, the actual prints, and analyze them in a way that would inform something that was objective.”

After acquiring the original cameras, Mr. Crawley painstakingly tested whether they were capable of producing images as crisp and recognizable as those popularized by Mr. Gardner and Mr. Conan Doyle. In the end he determined that they were not, and that the darkroom alchemy ordered by Mr. Gardner had transformed the girls’ amateurish blurs into marketable fairies.

In the early 1980s, amid the renewed attention, the cousins came clean. They first confessed privately to Mr. Cooper in interviews for his series in The Unexplained, a British periodical about the paranormal. In 1983, they admitted the hoax in The Times of London.

The girls’ plan had been absurdly simple: they used fairy illustrations from a book, which Elsie, a gifted artist, copied onto cardboard, cut out and stuck into the ground with hatpins. They had never set out to deceive anyone beyond their own families.

To the end of her life, Frances, who died in 1986, maintained that the fifth photo in the series was genuine. Elsie, who died in 1988, said that all were fakes.

Two of the three cameras used by the girls are now on permanent display at the National Media Museum in Bradford.

In the course of his work, Mr. Crawley befriended Elsie, then in her 80s. His writings about the hoax, though rigorously scientific, display great tenderness toward the two country girls whose idle boast of seeing magical creatures captivated a nation convulsed by war and modernity.

“Of course there are fairies — just as there is Father Christmas,” Mr. Crawley wrote in the British Journal of Photography in 2000. “The trouble comes when you try to make them corporeal. They are fine poetic concepts taking us out of this at times too ugly real world.”

“At least,” he went on to say, “Elsie gave us a myth which has never harmed anyone.”

“How many professed photographers,” he added, “can claim to have equaled her achievement with the first photograph they ever took?”

Geoffrey Crawley

Adjusted Physics?

Sir Arthur Doyle...Spiritualism...Cottington Fairies

- Sherlock Holmes And Chemistry

"Sherlock Holmes knew chemistry" by James F. O’Brien April 8th, 2013 Oxford University Press Sir Arthur Conan Doyle claimed that he wrote the Sherlock Holmes stories while waiting in his medical office for the patients who never came. When this...

- The Strand Magazine...january 1891 To March 1950...711 Issues

Agatha Christie, H. G. Wells, P. G. Wodehouse, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle were published in this quarterly journal.The Strand Magazine [Wikipedia]Here is a complete issue...January to June 1895...

- Deceased--leroy Grannis

LeRoy Grannis August 12th, 1917 to February 3rd, 2011 "LeRoy Grannis dies at 93; photographer documented California surf culture of the 1960s and '70s" The images by photographer LeRoy Grannis helped popularize and immortalize the sport —and...

- A Swiss Doyle

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle May 22nd, 1859 to July 7th, 1930 Scottish novelist, physician, spiritualist. His fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes, emulates the scientist, diligently searching through data and to make sense of it. "It is a capital mistake...

- Adjusted Physics?

I am sure you will agree that most of the so-called paranormal material is focused on entertainment and the acquisition of bucks. That doesn't mean that there aren't events that are truly “odd or unusual”--beyond the range of current knowledge...