Philosophy

On the list of tales we like to tell about Albert Einstein, the story of his "biggest blunder" is near the top. It begins with a problem that was bugging Einstein: How could his theory of general relativity be true and, yet, the universe stable? If his theory was right, the universe would have collapsed -- it could not possibly remain fixed, as physicists at the time believed it was.

To make his equations work, in 1917 Einstein introduced an additional term into them, expressed by the Greek letter lambda-- the "cosmological constant." The new term represented a repulsive force that would counter gravity's attraction, leaving the universe intact.

But in the years that followed, evidence mounted that the belief in the universe's motionlessness was wrong: The universe was, in fact, expanding. Had Einstein stuck with the equation before him, he might have been the one to intuit this central feature of the cosmos, but instead he concocted a contrivance in order to preserve a false assumption. Einstein, the story goes, called it the "biggest blunder" of his entire life, and that phrase (or close variations of it) has been repeated thousands of times, in books and journal articles across the disciplines.

The only problem is: Einstein may never have uttered the phrase "biggest blunder."

Astrophysicist and author Mario Livio can find no documentation that puts those words into Einstein's mouth (or, for that matter, his pen). Instead, all references eventually lead back to one man, physicist George Gamow, who reported Einstein's use of the phrase in two sources: his posthumously published autobiography My World Line (1970) and a Scientific American article from September 1956.

This, for reasons Livio recounts in detail in his new book Brilliant Blunders, is some seriously thin sourcing. For one, Gamow, brilliant physicist though he might have been, had a bit of a reputation for, shall we say, antics. Once, for example, Gamow had teamed up with a student of his named Ralph Alpher to write a paper. "He then realized," Livio told me, "that if he were to add as a co-author another known astrophysicist, whose name was Hans Bethe, then the three names would be Alpher Bethe Gamow, like alpha beta gamma, even though Hans Bethe had nothing to do with that paper." (His first wife, Livio writes, once remarked, "In more than twenty years together, Geo has never been happier than when perpetuating a practical joke.")

Knowing this about Gamow made Livio suspicious. What are the chances that Gamow, this ham, was retelling Einstein's confession with veracity? Not good, Livio found.

Livio looked at almost every single paper that Einstein ever wrote, including making a trip to the Einstein archive in Jerusalem to look at the collection personally. "And nowhere did I ever find the phrase 'biggest blunder', " Livio told me. "I didn't find it -- anywhere."

So he turned his attention to the correspondence between Einstein and Gamow, and it is at this point that Gamow's story begins to look even worse. "When might Einstein have used this expression with Gamow?" Livio writes in the book. As Gamow tells it in his autobiography, he and Einstein were quite close, with Gamow visiting the aging scientist every other Friday as the liaison between the Navy and Einstein during World War II. "He describes what good friends they were, how Einstein would greet him in one of his soft sweaters, and so on," Livio explains.

"Well, guess what," he continues. "I discovered a small article published in some obscure journal of the Navy by somebody named Stephen Brunauer," a scientist who had recruited both Einstein and Gamow to the Navy. In that article, Brunauer wrote, "Gamow, in later years, gave the impression that he was the Navy's liaison man with Einstein, that he visited every two weeks, and the professor 'listened' but made no contribution -- all false [emphasis added]. The greatest frequency of visits was mine, and that was about every two months." Clearly, Livio says, Gamow exaggerated his relationship with the famous physicist.

The correspondence between Einstein and Gamow seems to confirm this. The letters are quite formal, not those of the sort that would pass between intimate friends. Einstein was polite but not particularly effusive. "So wait a second," Livio says doubtfully, "Einstein never used this phrase with any more intimate colleagues, but he used it with Gamow?"

"Look," Livio emphasized to me, "it is impossible -- absolutely impossible -- to prove beyond any doubt that somebody did not say something. I don't claim that I proved it. But I think that it is highly unlikely that Einstein ever used this phrase."

Moreover, this is not to say that Einstein was at ease with the cosmological constant. "I'm not saying he didn't regret it," Livio says. "He definitely regretted it. He wrote about that to a number of friends. He thought it was ugly."

But to say it was his "biggest blunder" implies a level of regret that it seems Einstein did not feel. By contrast, when he did write about the error (which, it should be noted, in more recent years, has turned out to be less clearly an error than Einstein thought, but that's a whole other story), he did so with a dispassionate tone that conveys comfort with the notion that science would overturn some of his work. In a 1932 paper with Willem de Sitter, Einstein wrote, "Historically the term containing the 'cosmological constant' ? was introduced into the field equations in order to enable us to account theoretically for the existence of a finite mean density in a static universe. It now appears that in the dynamical case this end can be reached without the introduction of ?." And that was that.

There was, however, one regret that stood out for Einstein, and it had nothing to do with the elegance of his calculations. After a visit with the scientist at Princeton on November 16, 1954, Linus Pauling wrote in his diary: "He said that he had made one great mistake -- when he signed the letter to Pres. Roosevelt recommending that atom bombs be made; but that there was some justification -- the danger that the Germans would make them."

Scientific mistakes, Einstein's attitude implies, resolve with time. Mistakes of conscience, on the other hand, well, those are harder to undo.

- Heretofore Unpublished Einstein Paper [1931] And Commentary

Abstract... We present a translation and analysis of an unpublished manuscript by Albert Einstein in which he proposed a 'steady-state' model of the universe. The manuscript appears to have been written in early 1931 and demonstrates that...

- Albert Einstein's Methodology

Abstract... This paper discusses Einstein's methodology. The first topic is: Einstein characterized his work as a theory of principle and reasoned that beyond kinematics, the 1905 heuristic relativity principle could offer new connections between...

- Einstein & Religion...an Easter Offering

Just an offering during this movable feast...an article by M. Barone... Abstract: While Special and General Relativity are well known by a very large number of people, Einstein's religious convictions are almost ignored. The paper focuses on what...

- George Gamow...big Bang...popular Science

I almost forgot. This is George Gamow's birthdate. The Russian/American nuclear physicist George Gamow was born Mar. 4, in Odessa, in the Ukraine. Gamow came to the United States in the 1930s. During the War, when all the American nuclear physicists...

- "a Brain Is A Terrible Thing To Lose"--al Gore

I might as well address this issue for it inevitably comes up in discussions about Einstein and that is the story of Einstein's brain. Einstein died on April 18th, 1955 at the age of seventy six in Princeton, New Jersey from heart failure. An autopsy...

Philosophy

Did I say that?...an Einstein quote

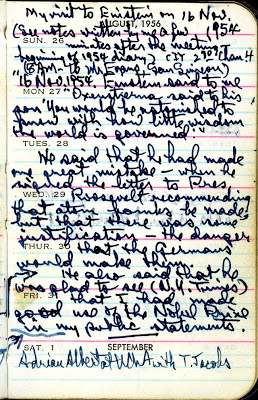

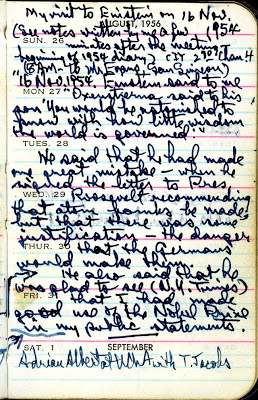

Linus Pauling's diary entry for November 16th, 1954.

"Einstein Likely Never Said One of His Most Oft-Quoted Phrases"

by

Rebecca J. Rosen

August 9th, 2013

"Einstein Likely Never Said One of His Most Oft-Quoted Phrases"

by

Rebecca J. Rosen

August 9th, 2013

The Atlantic

On the list of tales we like to tell about Albert Einstein, the story of his "biggest blunder" is near the top. It begins with a problem that was bugging Einstein: How could his theory of general relativity be true and, yet, the universe stable? If his theory was right, the universe would have collapsed -- it could not possibly remain fixed, as physicists at the time believed it was.

To make his equations work, in 1917 Einstein introduced an additional term into them, expressed by the Greek letter lambda-- the "cosmological constant." The new term represented a repulsive force that would counter gravity's attraction, leaving the universe intact.

But in the years that followed, evidence mounted that the belief in the universe's motionlessness was wrong: The universe was, in fact, expanding. Had Einstein stuck with the equation before him, he might have been the one to intuit this central feature of the cosmos, but instead he concocted a contrivance in order to preserve a false assumption. Einstein, the story goes, called it the "biggest blunder" of his entire life, and that phrase (or close variations of it) has been repeated thousands of times, in books and journal articles across the disciplines.

The only problem is: Einstein may never have uttered the phrase "biggest blunder."

Astrophysicist and author Mario Livio can find no documentation that puts those words into Einstein's mouth (or, for that matter, his pen). Instead, all references eventually lead back to one man, physicist George Gamow, who reported Einstein's use of the phrase in two sources: his posthumously published autobiography My World Line (1970) and a Scientific American article from September 1956.

This, for reasons Livio recounts in detail in his new book Brilliant Blunders, is some seriously thin sourcing. For one, Gamow, brilliant physicist though he might have been, had a bit of a reputation for, shall we say, antics. Once, for example, Gamow had teamed up with a student of his named Ralph Alpher to write a paper. "He then realized," Livio told me, "that if he were to add as a co-author another known astrophysicist, whose name was Hans Bethe, then the three names would be Alpher Bethe Gamow, like alpha beta gamma, even though Hans Bethe had nothing to do with that paper." (His first wife, Livio writes, once remarked, "In more than twenty years together, Geo has never been happier than when perpetuating a practical joke.")

Knowing this about Gamow made Livio suspicious. What are the chances that Gamow, this ham, was retelling Einstein's confession with veracity? Not good, Livio found.

Livio looked at almost every single paper that Einstein ever wrote, including making a trip to the Einstein archive in Jerusalem to look at the collection personally. "And nowhere did I ever find the phrase 'biggest blunder', " Livio told me. "I didn't find it -- anywhere."

So he turned his attention to the correspondence between Einstein and Gamow, and it is at this point that Gamow's story begins to look even worse. "When might Einstein have used this expression with Gamow?" Livio writes in the book. As Gamow tells it in his autobiography, he and Einstein were quite close, with Gamow visiting the aging scientist every other Friday as the liaison between the Navy and Einstein during World War II. "He describes what good friends they were, how Einstein would greet him in one of his soft sweaters, and so on," Livio explains.

"Well, guess what," he continues. "I discovered a small article published in some obscure journal of the Navy by somebody named Stephen Brunauer," a scientist who had recruited both Einstein and Gamow to the Navy. In that article, Brunauer wrote, "Gamow, in later years, gave the impression that he was the Navy's liaison man with Einstein, that he visited every two weeks, and the professor 'listened' but made no contribution -- all false [emphasis added]. The greatest frequency of visits was mine, and that was about every two months." Clearly, Livio says, Gamow exaggerated his relationship with the famous physicist.

The correspondence between Einstein and Gamow seems to confirm this. The letters are quite formal, not those of the sort that would pass between intimate friends. Einstein was polite but not particularly effusive. "So wait a second," Livio says doubtfully, "Einstein never used this phrase with any more intimate colleagues, but he used it with Gamow?"

"Look," Livio emphasized to me, "it is impossible -- absolutely impossible -- to prove beyond any doubt that somebody did not say something. I don't claim that I proved it. But I think that it is highly unlikely that Einstein ever used this phrase."

Moreover, this is not to say that Einstein was at ease with the cosmological constant. "I'm not saying he didn't regret it," Livio says. "He definitely regretted it. He wrote about that to a number of friends. He thought it was ugly."

But to say it was his "biggest blunder" implies a level of regret that it seems Einstein did not feel. By contrast, when he did write about the error (which, it should be noted, in more recent years, has turned out to be less clearly an error than Einstein thought, but that's a whole other story), he did so with a dispassionate tone that conveys comfort with the notion that science would overturn some of his work. In a 1932 paper with Willem de Sitter, Einstein wrote, "Historically the term containing the 'cosmological constant' ? was introduced into the field equations in order to enable us to account theoretically for the existence of a finite mean density in a static universe. It now appears that in the dynamical case this end can be reached without the introduction of ?." And that was that.

There was, however, one regret that stood out for Einstein, and it had nothing to do with the elegance of his calculations. After a visit with the scientist at Princeton on November 16, 1954, Linus Pauling wrote in his diary: "He said that he had made one great mistake -- when he signed the letter to Pres. Roosevelt recommending that atom bombs be made; but that there was some justification -- the danger that the Germans would make them."

Scientific mistakes, Einstein's attitude implies, resolve with time. Mistakes of conscience, on the other hand, well, those are harder to undo.

- Heretofore Unpublished Einstein Paper [1931] And Commentary

Abstract... We present a translation and analysis of an unpublished manuscript by Albert Einstein in which he proposed a 'steady-state' model of the universe. The manuscript appears to have been written in early 1931 and demonstrates that...

- Albert Einstein's Methodology

Abstract... This paper discusses Einstein's methodology. The first topic is: Einstein characterized his work as a theory of principle and reasoned that beyond kinematics, the 1905 heuristic relativity principle could offer new connections between...

- Einstein & Religion...an Easter Offering

Just an offering during this movable feast...an article by M. Barone... Abstract: While Special and General Relativity are well known by a very large number of people, Einstein's religious convictions are almost ignored. The paper focuses on what...

- George Gamow...big Bang...popular Science

I almost forgot. This is George Gamow's birthdate. The Russian/American nuclear physicist George Gamow was born Mar. 4, in Odessa, in the Ukraine. Gamow came to the United States in the 1930s. During the War, when all the American nuclear physicists...

- "a Brain Is A Terrible Thing To Lose"--al Gore

I might as well address this issue for it inevitably comes up in discussions about Einstein and that is the story of Einstein's brain. Einstein died on April 18th, 1955 at the age of seventy six in Princeton, New Jersey from heart failure. An autopsy...